Is brand resurrection the future?

Planned comeback or nice accident?

People constantly look to the past. And there are good reasons to do so – it’s a cultural necessity to fold back a bewildering future to let the past catch up.

Brands also harness memories of old products or assets, intentionally or unintentionally. British food label Branston recently reverted to its 1970s slogan “Bring out the Branston”. Burger King revived a logo from 1969. Even the US army decided to revive an early-80s slogan, “Be all you can be”.

Sometimes consumer demand is enough to make firms look to the past. Petitions or Facebook pages beg for a television series or old recipe to be brought back.

Other-times nostalgia is a pragmatic rather than sentimental move. It makes sense to return to brand assets and campaigns that marked periods of success.

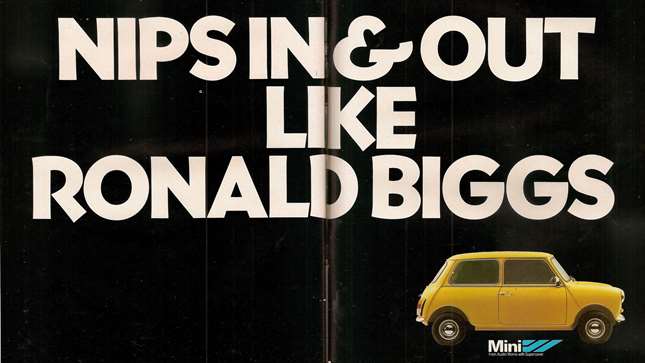

For cherished but inactive brands, often all that’s needed is a change of management. Two decades after the Mini’s golden era in the 1960s it was abandoned by the Austin Motor Company as fashions changed. BMW acquired the brand in the mid-90s and spent a full five years developing a revamped model.

While tremendous amounts of work went into modernising the vehicle, little R&D was needed in the marketing department.

Even though the 2000s weren’t notable for 1960s mania, the car was a strongly recognisable, undeniably British symbol of the past.

The message here is simple: if you have an asset this powerful, you don’t need excessive reinvention. Simply identify the good parts and make it compatible with today.

Some “hipster” brands such as Polaroid, Pabst Blue Ribbon and so on were earnestly brought back in the early 2010s in the US (though here in the UK direct nostalgia wasn’t such a big factor). Through music, film and other old media, millennial consumers had convinced themselves that these brands represented a purer, more authentic way of doing things – although those who grew up using Polaroid cameras would probably disagree.

For the brands themselves, this was an exercise in distribution rather than marketing strategy. Put Pabst on tap in bars or venues young people would frequent. Make Polaroid cameras and film available in Urban Outfitters branches.

In an era where flea markets and antique shops dominate, openings for new, revived products that slot into these lifestyles are plentiful.

For the craftier brands out there, the hazy, poorly documented past may allow for a little creative licence. Today, Salomon and Mizuno – brands that until recently you’d see only runners wearing – have gone for a lifestyle angle. Their advertising hints at a past in which their shoes were heavily sought-after, but recollections vary.

Last year, McDonald’s sought to capitalise on nostalgia in its own way. It released a Happy Meal for adults. In collaboration with a younger fashion brand, Cactus Plant Flea Market, it released full-sized meals that came with collectable plastic figurines.

The campaign was buoyed by the collaborator and the notion of collectability, and the meals sold out quickly.

It sounds laughable but it worked well. While the campaign was probably a loss-leader, it successfully lured people back into the restaurant who were far too old to be buying Happy Meals and who may indeed have stopped eating at McDonald’s altogether.

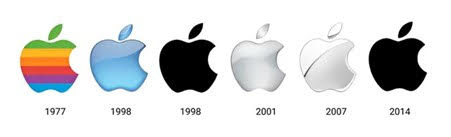

Sometimes it has nothing to do with nostalgia at all. In its drive for a flat, minimal logo, all Apple had to do was look back through its archive. Again, we fold back the future to let the past catch up – and it feels good.

Even if they feel what they do is timeless, unsusceptible to fashion, businesses need to remind themselves that appetites can be fickle and a sudden peak in interest doesn’t say anything about the long term.

Our final example, Koss Porta Pro headphones, has received an enormous, organic push on Pintrest and TikTok as a budget retro-futuristic option.

Despite coming out in the 1980s, the headphones appear never to have left production. Now, Koss could go crazy to meet renewed demand. But should it? Social media popularity comes and goes, fast.

This is an example of a brand not doing anything on purpose. It can therefore afford to sell the product at an attractive price – almost half of what it was in the 80s. In doing so, it can make the most of its renewed interest.

As much of this article has proved, moving with the times doesn’t pay off every time.