Was McLuhan joking?

A guru reassessed

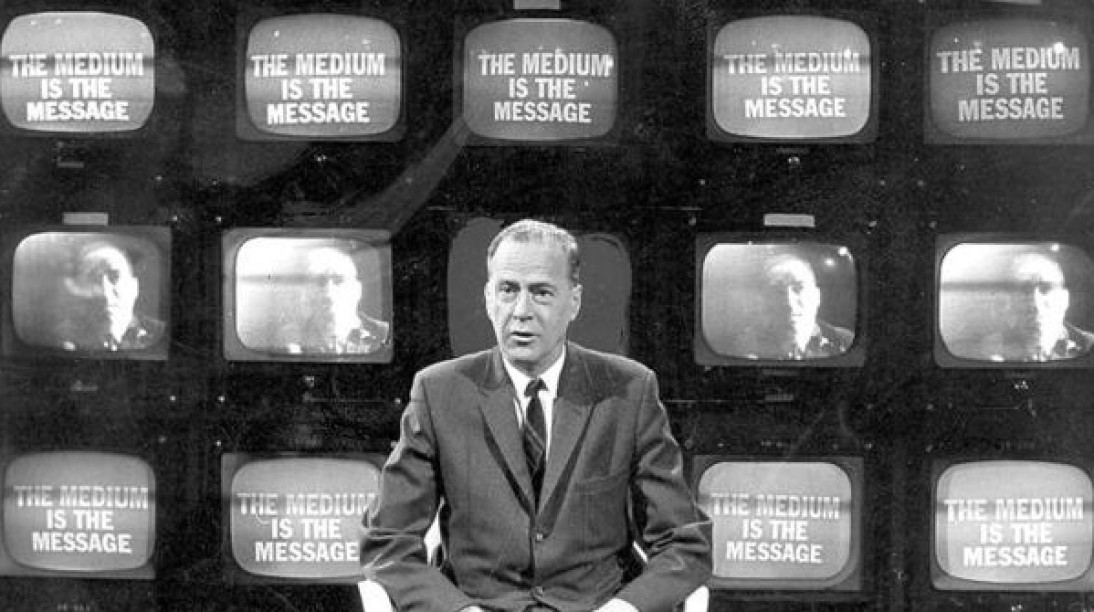

In 1965, the great essayist Tom Wolfe wrote a fabulous piece about Marshall McLuhan. Few people under 40 have probably heard of McLuhan, but his influence is everywhere. McLuhan, a bookish Canadian academic and James Joyce obsessive, invented media theory and the idea of technological modernity.

He was a digital guru before there were such people and was right about most things. But not his most famous pronouncement.

Wolfe loved McLuhan and hoopla that accompanied his visits to the US, where he spoke to advertising and business leaders.

In the essay What If He Is Right?, Wolfe gets to the heart of McLuhan's argument. What was shown on a medium like TV was irrelevant, explained Wolfe. It was the psychological effect of allowing oneself in to its embrace that counted.

Wolfe says: “It doesn't matter about the content. The most profound effect of television – its real 'message', in McLuhan's terms – is the way it alters men's sensory patterns. The medium is the message – that is the best- known McLuhanism. The world is growing into a huge tribe, a ... global village, in a seamless web of electronics.”

This is brilliant stuff. Lordy, that paragraph stands up pretty well today, 50 years later. The idea that media and distribution alter our perception. That the world was being made smaller by technology. Then the final phrase “a seamless web of electronics”.

The use of the words “content” and “web” alone mark him out as an uber-guru. Hell, he was right.

McLuhan said lots of other clever stuff, much of which still makes sense. He saw the invention of movable type by Johannes Gutenberg as the start of a media explosion that culminated in TV and computers.

Phonetic language, he reckoned, separated people from a balanced sensory environment. Television returned man to a tribal, emotionally volatile state. The coracle, a suit of armour, the car – and naturally the computer – were extensions of man’s central nervous system. Every new technology needed a new war.

It’s no co-incidence that many of these ideas are mainstream in the digital age – even if their inventor is not so well known. Many of pioneers of the brave new technological frontier read his stuff. He influenced Andy Warhol, Timothy Leary and Jean Baudrillard.

But, he wasn’t right about everything. His best-known slogan "the medium is the message" – that media distribution technology matters more than its content – is unarguable as a prediction.

We are obsessed with every new device and app that comes along. Our lives are corroded and overheated by technology. Addiction to digital devices is as pervasive as a tobacco habit, if not quite so unhealthy.

McLuhan hastened the phoney adoption of the new. The way we queue for a new mobile and delight in its minute improvements is as undignified as children lunging for a sugar rush.

It will perhaps take 100 years to get used to technology. But the medium is, nonetheless, not the message, even if we think it is. The spark of imagination, the accident of creativity, the carving of individual beauty are still vastly more important that the medium in which they are delivered. Now we yearn for the hand-made, the real, the sensory, the old.

McLuhan himself seems to have treated his most notorious slogan as a bit of a joke, abbreviating it punnily to “The medium is the mass age”, “The medium is the mess age” and “The medium is the massage”. He said he wasn't necessarily issuing statements of truth, merely making "probes".

So was he having a laugh all along?