Cave art to tractors

Our history of content

So where did the notion of content marketing begin? It depends what you mean by content. It can fall anywhere between informative and helpful for the consumer – or borderline propaganda on the part of the creator.

This list will attempt to clarify key moments in format, technique and motive that led to the online articles, lists and features synonymous with content today.

Lascaux Cave Paintings – circa 15,000BC

Lascaux, France boasts a series of remarkable murals. We see a striking command of colour, space and texture in the Lascaux murals that give new meaning and emotion to the animals depicted. Rather than a mirror to the outside world, there is a tangible aura given to the cattle and horses.

It is impossible for us to ever know Lascaux’s true purpose. Information for the hunter? Possibly. Worship? Likely. Celebrating the hunter’s command of the animal? Also likely. Either way, it is information with purpose. So, it is content.

Lindisfarne Bible – 710s

The Lindisfarne Bible, originating from the minute island of the same name in Northumberland, marks a key point in the combination of decorative aesthetics and text. The manuscript, which is estimated to come to fruition in the 710s, is thought to be a dedication to the Bishop Cutherburt, a resident on the island.

Beyond its obvious ceremonial utility this particular Bible it had a hand in starting the phenomenon of non-essential images being used to complement texts. In this way texts could still be of use to the illiterate or those in the process of learning to read. Content, then.

The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli – 1532

Machiavelli's The Prince holds great significance in political science, but what does it mean for the history of content? It functions like a Wikihow entry for a successful authoritarian rule, detailing how to appear as a ruler, the accumulation of new territory and dealing with a populace. Machiavelli offers different paths one can take, by virtue or by force for example.

Countless times academics have taken the text as a work of satire, a collection of negations to a science concerned with eliminating immoral behavior. However, this is perhaps due to its wider circulation after its original publication. If Machiavelli were being sincere why would a work like this leave the circle of elites it was intended for?

The Lives of the Artists by Giorgio Vasari – 1550

Giorgio Vasari's illuminating documentation of Renaissance masters provides a turning point for informative content.

Aside from maintaining that the work of these artists as vital and important, Vasari is free to risk accuracy, perhaps even historical credibility, in his unique representation of the artists included. Gossip is intertwined with documentation of the practices and culture of the sculptors, painters and innovators of the period. In this respect the text is not far from the lifestyle vlogs that dominate YouTube today, the social fabric of the age is revealed and Vasari's personal relations and views are worn on his sleeve.

Life of Samuel Johnson by James Bowell – 1791

Regarded as the precursor of the modern biography, this mythologising of the great man of letters is highly entertaining and possibly partially inaccurate. Boswell, it has to be said, only met Johnson in 1763, when the originator of the dictionary was 54.

Nonetheless, it is this work which has kept Johnson’s image alive over the past 200 years. In that sense it is a work of marketing and PR – albeit a highly entertaining and engaging one. So undoubtedly content.

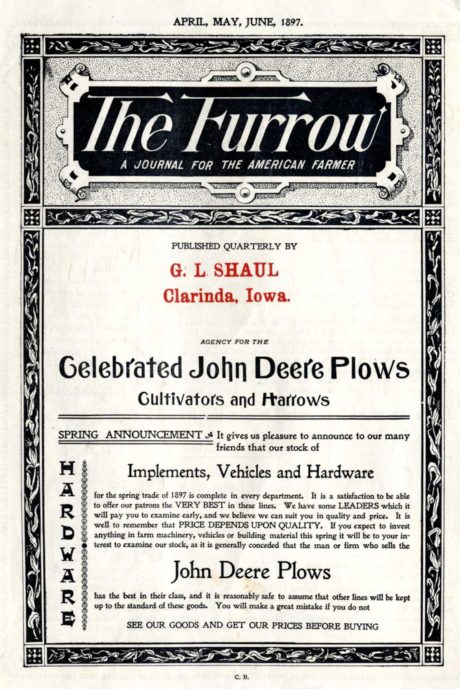

The Furrow, published by John Deere – 1895 onwards

Farming equipment manufacturer John Deere's catalogue-cum-publication The Furrow is cited by many as one of the key transitions from a purely advertorial magazine to a broader, informative publication. The Furrow was extremely successful, surpassing a circulation of 4 million. Farmers liked that it had articles instructing how to maintain a farm and a breakdown of uses of equipment rather than just a list of prices and specifications.

Pear's Cyclopedia – 1897 onwards

Last published in 2017, Pear's compact encyclopedia was originally called the Shilling Cyclopedia. Coupling historical, anthropological, scientific and cultural sections with disparate and obscure subjects it has made for an incredibly informative compendium of information, with Penguin going so far as to call it 'the Swiss army knife of reference books'.

Considerably smaller and lighter, and limited to a single volume, the annual Cyclopedia has been able to deliver its information quickly and portably. In the Victorian mind, the brand extension from soap manufacturer to purveyor of knowledge must have been quite natural. Cleanliness and education went hand in hand.

Michelin Guide – 1990 onwards

Like the Cyclopedia, the Michelin guide is an annually produced guide active for over 100 years but, contrary to the wide content of Pear's, it specialises in restaurants and hotels and was the first of its kind. The star system, by far the most infamous component of Michelin's survey has the notoriety to harm or improve a reputation of a business.

As one would imagine three stars are usually reserved for extremely expensive premises, but Michelin branched out in 1955 to include a 'Bib Gourmand' category for star-worthy dishes under a certain region-specific price. This sign of quality could reach wider audiences and expand the network of restaurants without compromising the integrity of the stars. It’s a brilliant piece of brand extension for a tyre manufacturer. Somewhere to go on our pneumatics.