Chatbots charm

Humans don't always

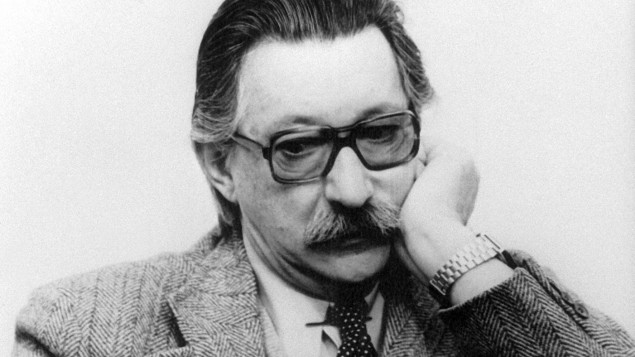

One day in January 1966, Joseph Weizenbaum, the distinguished MIT computer scientist and artificial intelligence pioneer, decided to play a joke. He wrote a spoof therapy program.

Users could type in thoughts and the robo-shrink would respond with follow-up questions. It was in effect "mirroring", saying things the user wanted to hear. The program was called Eliza, after the character in George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion.

Everyone who tried it loved it. They felt the machine really understood them and trusted it enough to tell it their most intimate secrets. A particular enthusiast was Weizenbaum 's PA, who on one occasion asked him to leave the room so she could continue her conversation with the machine.

When Weizenbaum told her that he'd written the code as a prank and that he had a log of the conversations, she was outraged, saying her confidence had been breached.

So even on the first minutes of the first day in humankind's great experiment with machine learning, people adored robots. As Weizenbaum (above) put it: "I had not realised ... that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people." You can try Eliza here. It's like talking to Alexa's grandmother.

The term anthropomorphism describes man's tendency to attribute human qualities to animals and objects. Thinking kittens behave like babies, for instance.

It's probably one of our greatest skills, giving us empathy with other creatures so we may all the better exploit them.

We do a similar thing with tools, seeing them as friends. Stone Age hunters saw their axes and spears as extra appendages in the battle for survival. We treat cars and phones in a similar way.

The 1960s futurologist and technology visionary Marshall McLuhan called this "the extensions of man" – armour, weapons, the coracle and television all connecting the cerebral cortex with fellow humans and the world in an electric embrace.

Artificial intelligence will be the apex of the extensions of man.

The question is: will man have overextended himself? Will it be like the spider plant which creates many baby plants only for them to sever their botanical umbical cords, grow and starve the parent plant of nutrients till it shrivels and dies.

Google's research into AI and translation hit a milestone recently. Its machine translation now has a bridging language, a bit like Esperanto. The machine translates the first tongue into the common language before translating into the destination language. This makes it easier to detect connections between languages and understand grammar.

Anyway, some commentators suggest, it decided to do this itself, without human instruction.

Here is the fear. Machine learning will be beyond good and evil. It will use disinterested cold logic to achieve its aims. We are doomed. Want to solve the problem of congested cities? Easy. Just decongest them.

I don't think so. We shouldn't fear AI anymore than we should fear the Great Library at Alexandria or the Gutenberg Bible.

Just like all other extensions of man, AI will coalesce and amalgamate knowledge and ambition. It will merge and link human thought. It will solve problems.

Its dark side, if it has one, will be a result of human nature not the cold steel of robot logic as exhibited by Niska in C4's Humans (above).

As with Eliza, people will feel comfortable, possibly more comfortable, communing with machines. Its greatest immediate use will be in medicine, harnessing data and research into personalised treatment.

It has, however, the potential to imitate and exaggerate humanity's tribal tendencies, as does social media. Just as automated share trading systems need to be shut down occasionally when they go into overdrive, so should social media and AI. Instead of a flash crash, we should be aware of flash bigotry and hate.

Innovation is sometimes driven by curiosity but more often than not necessity and utility are the inspiration. We overcome our fears and see the good in technology.

When trains first started operating, dairy farmers feared the noise would curdle milk. The first street lights prompted protests about loss of privacy. Both worked out well.

Eliza's inventor was trying to show AI was a bad thing. That was perhaps an expression of the pessimism of the times.

Compared to the gun or the hydrogen bomb, however, it is benign.

We will come to see it as good. As long as we are good.