Can you own your brand’s colour?

The law’s not black and white

A split second peek at a shopfront banner, shopping bag, lorry or food wrapper is sometimes enough to tell you all you need to know. In the same way GCSE students might highlight passages in their revision, brand colours compartmentalise and retain associations. Getting it right is a real art – Highbrook Media was tinkering with its palette for weeks.

Different people may have different interpretations but basic colours broadly mean the same things to us – red means speed, vigour, passion. Brown means hard-wearing, dependable, a brand with history. But once you’ve settled on the perfect hue for your story how do you own it? And can you stop others using it?

There are global differences but even within legal jurisdictions there is still confusion over whether you can truly trademark a colour. For the most part, colour has been used more as a key characteristic in deliberations rather than the sole basis for a dispute.

The University of Texas, who use a lovely burnt orange, used their colour to shut down third party iPhone apps aimed at university students, iTexas being one of them. Would they have had a point if the apps used orange alone? If it weren’t for the use of the word ‘Texas’, they may have been little basis.

Yes, the colour was trademarked but the university must have benefited from it becoming embedded in the local community. Students, local residents and supporters of the Texas Longhorns probably don’t see orange as discreetly belonging to the University of Texas.

In most cases, colours themselves are not enough for a legal claim. Do UPS and T-Mobile come to mind instantly when looking at our new logo mockups?

Of course, the argument, as with many IP or image disputes, is that consumers may be confused.

With one of their trademarks in 1998, UPS made sure competitors in the delivery industry couldn’t use their colour combination. A driver dressed in head to toe in that particular brown with a brown and yellow van on the pavement behind them might be misleading, and you’d understand why UPS might take action. To date, they haven’t gone after anyone exclusively on the basis of colour.

Deutsche Telekom is a more extreme example. Type ‘deutsche telekom magenta threaten’ and you’ll find a long list of global firms harassed. A smartwatch producer, technology blog, insurer, IT support specialist and invoice management firm are just some of the examples. The worst part is that in many cases it wasn’t even the exact shade used by T-Mobile. It’s understandable if a competitor used #E10075, but it’s not unfair to say these tactics border on patent trolling.

Difference between decoration and identification

The distinction is between ‘nice to have’ or ‘an extra bit of flair’ and ‘essential to telling our story’ or ‘a central component of brand recognition’. Where the line lies between these two is difficult to say.

It’s also worth noting that it’s not as simple as founding a company, choosing a hex code you like and contacting the Intellectual Property Office in your jurisdiction. You need to have entered the public imagination already. While this is not a measurable barrier to entry, all the aforementioned examples spent decades building brand awareness. Paul Smith has been using stripes since the 1970s, but only trademarked a highly recognisable combination under EU law in 2002.

The story of brand and colour is certainly not chicken and egg. Colour selection, wider branding and history work together to create a story. Fonts, logo shapes and even company names come and go, but often you’ll find corporate colour schemes are only marginally revised.

Is it fair to judge a brand by its colour?

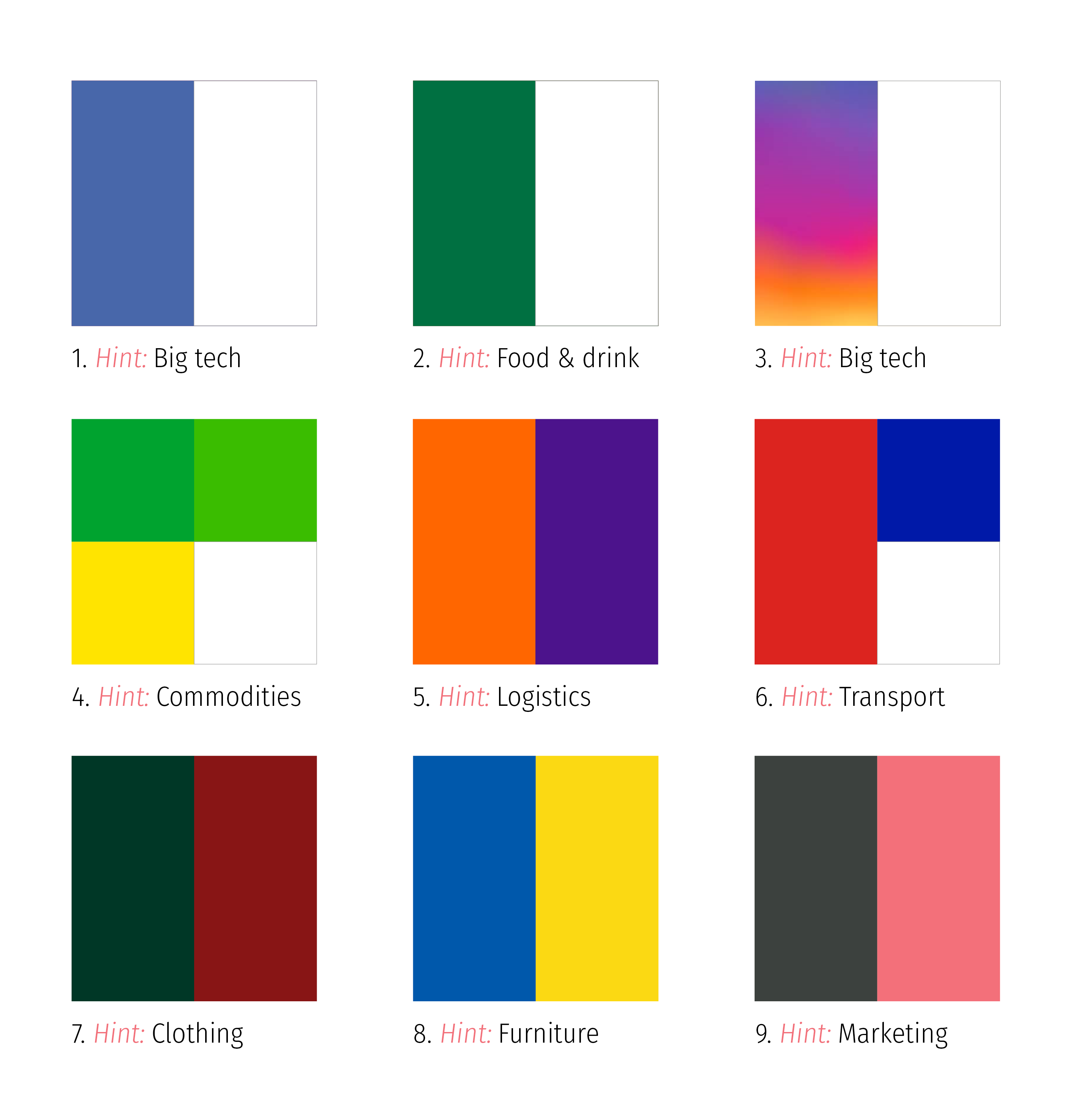

A lot of brand colours are instantly recognisable, but things change when logos are augmented and the palette is taken out of its usual context. See how many you can spot on our list below (no, number eight is not the Ukrainian flag):

When you're ready, check your answers here.