Italian modern art enjoys a renaissance

The Anthology section features some of our best writing for clients. This article for Aon explores why avant-garde Italian painting is achieving record prices at auction

AUTHOR: Alastair Smart

EDITOR: Rhiannon Edwards

Italian art used to mean the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, the glory days of the Renaissance, Mannerism and Baroque. However, an undeniable trend in the art market over the past few years has seen the rise of Italian art from the second half of the 20th century.

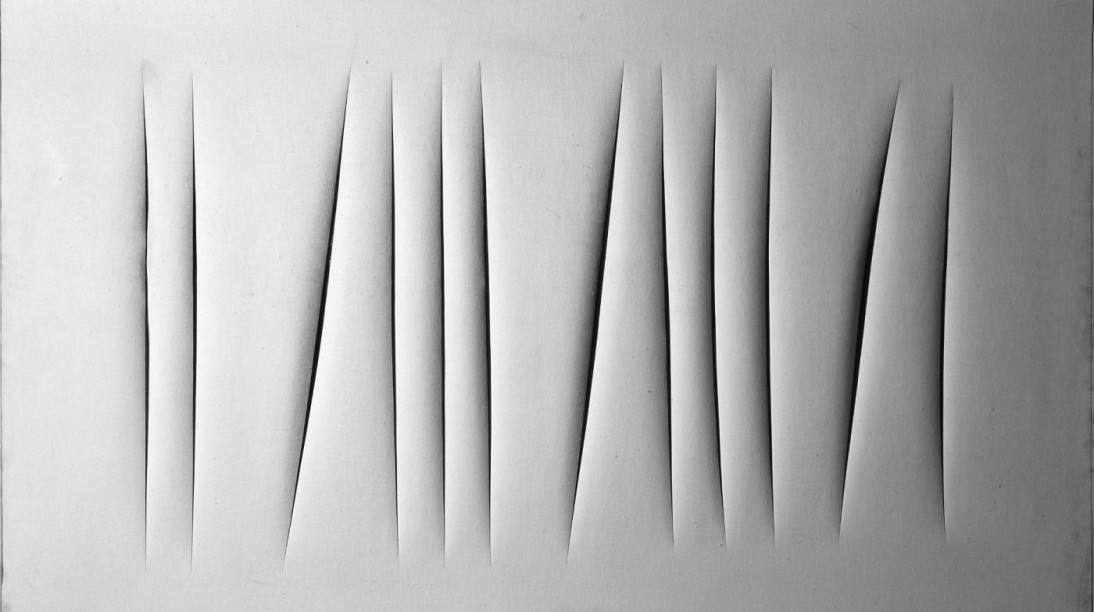

At auction after auction, artist-record prices have been achieved: Piero Manzoni with £12.6m for Achrome, in 2014; Lucio Fontana with £19.3m for Concetto Spaziale, La fine di Dio, in 2015; and Alberto Burri with £9.1m for Sacco e Rosso, in 2016.

Such works are a far cry from the art of the Renaissance. Fontana specialised in canvases slashed by a knife; Burri in works he partially set fire to.

We should consider also the figures for the annual autumn auctions of modern and contemporary Italian art at the main London houses. Where, at the turn of the millennium, these took £10m, in the past three years the average has been around £50m.

To what can we attribute this increase in value? Changes in Italian legislation earlier this decade certainly helped, removing protectionist barriers to selling art abroad. To a great extent, it has also been a case of the commercial catching up with the curatorial.

Which is to say that Italy's late 20th-century artists have received big museum retrospectives – Burri at New York's Guggenheim and Alighiero Boetti at London’s Tate Modern, with a Fontana show imminent at New York's Metropolitan Museum, too – and the market has simply responded. Decoration by an art institution so often prompts a surge in prices.

Also, when the artists in question were at their peak, in the Fifties and Sixties, the US was still deemed the centre of the art universe. Movements from Abstract Expressionism to Pop reigned, and the rest of the world didn't get much of a look in. Something compounded by the fact that the major art-history books were written and published in America, too.

Over time, though, and as a consequence of globalisation, it has come to be appreciated that artists from other nations also produced important, avant-garde work.

In the case of Fontana, Burri, Manzoni and Enrico Castellani – though there isn’t much in the way of brushwork or colour to speak of – they transformed painting as anyone knew it. Fontana and Burri in the manner already discussed, Manzoni by soaking canvases in kaolin solution and Castellani by driving nails into his.

A final thought: it's something of a cliché to say artists are ahead of their time, but it really does seem to apply here. The Italians’ minimalist aesthetic seems entirely in synch with the cool, clean-cut interior design so fashionable in houses today. Which is perhaps another reason for their rise. What was once deemed subversive and revolutionary now feels right at home.

FURTHER READING: Aon case study