Don’t be afraid of bad writing

Even great things have iffy beginnings

Many of us will have colleagues with seemingly limitless fluency in their writing. But even they don’t get it right immediately – they rewrite, revise and refine.

Maybe the real talent in writing is simply getting on with it rather than agonising. In other words: don’t be afraid of bad writing.

To be clear, Highbrook makes no excuse for publishing substandard work, but we’d argue that great things don’t always begin well. Having a starting and ending point that is fragmented, error-heavy and confusing is better than staring at a blank page for two hours.

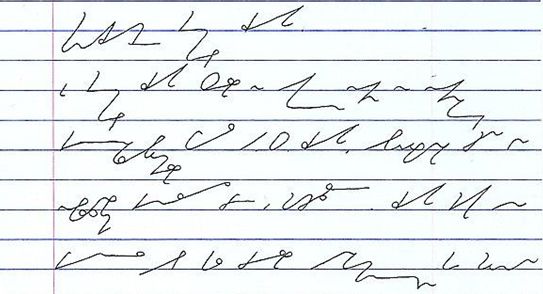

For Highbrook Media, jotting things down quickly is best. We comprise many current and ex-journalists. Many are versed in the dying language of shorthand (below).

While no one can look at this bizarre set of lines and say it’s “good writing”, this alternative language allows you to skip the dawdling and get everything down fast.

Urgency, speed – even nervousness when putting fingers to keyboard – are not things to dread or fear. Frantically mapping your message from start to finish can be far more effective than chipping away line by line, section by section. Indeed, urgency often improves writing.

That slightly ragged, off-the-cuff – but inherently human – quality is considerably more engaging than committee-written, committee-amended fluff.

What’s more, it’s the opposite of AI. And who wants to read writing by a robot that appears to have been force-fed the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Times in a darkened room? Not for nothing is Highbrook’s slogan “Clever content. Made by humans”.

So starting your project without taking yourself too seriously can lead to more variation and character.

But the stream-of-consciousness exercise has to end somewhere. Come up with a set of sentences you can string together and start arranging them into a structure, interrogating and fleshing out your points. Ask a colleague to take a look (telling them, of course, that it’s not finished).

A word of warning here, though: jotting your initial thoughts straight into a shared document such as Google Docs is not the best way to go. The pressure of picturing your colleagues waiting for you to come up with a brilliant idea is scarcely likely to inspire. Better to keep the sharing until later.

Finally, we’ve yet to mention the most positive aspect of quick, unfussy writing – there’s no real loss if you delete it.

Ten minutes sketching out a whole piece and being OK with scrapping half of it is far better than spending that time perfecting a paragraph only to Ctrl+A and delete the lot. In fact, it’s cathartic to be rid of stray sentences and flakey concepts.

We want 2024 to be full of notes on scraps of paper, doodles, writing in the margins, hundreds of notes on your phone. We can’t bear another year of empty white screens filled only with a slowly flickering cursor.

So get writing.

This piece was written in 15 minutes (more or less).

Whole books written in a month

A Clockwork Orange – Anthony Burgess

On The Road – Jack Kerouac

Casino Royale – Ian Fleming

A Study in Scarlet – Arthur Conan Doyle (the first Sherlock Holmes novel)

A Christmas Carol – Charles Dickens

Oh, and Shakespeare wrote King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra in a year. Not bad.

Books that took an awfully long time to write

Finnegans Wake – James Joyce (17 years)

The Lord of the Rings – J.R.R. Tolkien (17 years)

Les Miserables – Victor Hugo (17 years)

Gone with the Wind – Margaret Mitchell (10 years)

The Catcher in the Rye – J.D. Salinger (10 years)

Jurassic Park – Michael Crichton (8 years)